We fished through several resources to find the story swimming below the surface and hauled in 50 fish factoids about the lives of Oklahoma’s incredibly diverse native nongame fish, with a special focus on gar and buffalofishes. Dive into Oklahoma’s fishes to learn about their various survival strategies, mind-boggling records, how biologists balance the fishery, and how anglers have pitched in to help showcase the potential of Oklahoma’s populations.

Browse our 50 fish factoids:

- DIVE INTO OKLAHOMA’S FISHES

A boat load of fishes can be found in Oklahoma. While our fishes come in all shapes and sizes, each plays a valuable role in its community.

Image

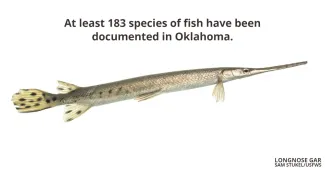

1. Oklahoma has an incredible diversity of native fishes. The smallest adult fish, the least darter, rarely grows longer than 1.5 inches while the largest fish, the alligator gar, can grow more than 8 feet in length.

2. Oklahoma also has an incredible diversity of waterways and fish habitat. Some fish are found only in clear, shallow streams; others can be found in murky soft-bottomed backwaters; and others still can tolerate high alkalinity and salinity levels. No matter how big or small, where they’re found in the state, or where they are in the food chain, each native species plays a valuable role in its community.

3. Feeding a diverse fish community calls for a diverse menu. Paddlefish and bigmouth buffalo filter plankton out of the water column; shovelnose sturgeon and smallmouth buffalo suction insects and other nutrients from the streambed; flathead catfish and longnose gar ambush other fish; and channel catfish live on the full buffet that can be found in Oklahoma’s waterways.

4. The plural of fish is “fish.” But “fishes” can be used to describe more than one species of fish.

5. At least 183 species of fish have been documented in Oklahoma. Only 16 of those species, including the hybrid saugeye and a handful of species not native to Oklahoma like northern pike and trouts, are considered “game fish.” The remaining 91% of Oklahoma’s fishes are considered “nongame fish” and are largely unregulated.

6. Four species of gar can be found in the state: the spotted gar, longnose gar, shortnose gar, and alligator gar, a species of greatest conservation need. Gars can survive in slower-moving, warmer waters with low dissolved oxygen levels because of their well-developed lung-like gas bladder and their ability to “gulp” for air. Such conditions are inhospitable for many freshwater species.

7. Sixteen species of native sucker fish can be found in Oklahoma. Most have downturned mouths – some comically so – and feed on the bottom of the river or lake. Suckers are most often found in eastern Oklahoma, but the river carpsucker can be found statewide.

8. Gar and buffalofishes have been unfairly considered “rough” or “trash” fish by generations of Oklahomans. Gar have been "trash-talked" for eating angler-preferred fish and the small forage species of sportfish. Similarly, buffalofishes have been held in low regard due to their unfortunate resemblance to nonnative carp. However, diet studies have found alligator gar predominately feed on gizzard shad, while most sucker fish feed on invertebrates and mussels on the bottom of rivers and lakes.

9. Buffalofishes and their relatives in the sucker fish family also may play an important role in the lifecycle of our freshwater mussel community. These fish can be hosts for mussel larvae, which helps redistribute the filter-feeding clams along our rivers.

- REELIN' IN THE YEARS

Many nongame fish have been overlooked in previous life history studies. New research has shattered our perceptions of how long some fish may live.

Image

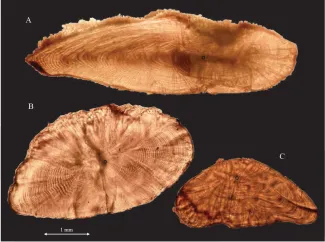

10. The oldest known freshwater fish is a 112-year-old bigmouth buffalo collected from Minnesota waters. Prior to this new maximum age estimate (published in 2019), the oldest known bigmouth buffalo was a 26-year-old individual collected from Oklahoma’s Keystone Reservoir in 1998. Filling knowledge gaps like maximum age estimates can help biologists better understand the survival and reproductive strategies of our fishes and better manage our native fish populations.

11. Oklahoma’s record smallmouth buffalo, caught in 2019, was found to be a 62-year-old female, and is was thought to be the oldest known individual of its species at the time*. The native fish was spawned in 1957, 11 years before the completion of Broken Bow Reservoir, the lake from which it was caught. By back calculating the length-at-age, biologists believe the fish had reached 50% of its total length by age 6, and 80% of its total length by age 17.

* This record was broken in 2023 when a 101-year-old smallmouth buffalo was documented from Arizona’s Apache Lake.

12. In 2018, Dustin Satton donated his then-record spotted gar, bowfished from Lake Arbuckle, to the Wildlife Department. Biologists determined the fish was a 43-year-old female, a new maximum age estimate for the species. An examination of the 2003, 2016, and 2018 state record spotted gars found the fish had grown to 38% of their total length in their first year, and 81% of their total length by age 6. Growth in each of these fish plateaued after age 16.

13. Biologists use the terms “age-verified” or “age-validated” to describe individuals of a known age. This can happen when a hatchery-reared fish is tagged and later recaptured, or by examining the fish for some kind of traceable environmental “mark” at a known time in the fish’s life. Otherwise, all ages are estimations.

14. To get estimates of fish age, biologists most often rely on the annual growth rings found on one of three pairs of otoliths or earstones found in each fish. After the earstones are removed from the fish, they’re sometimes browned on a hot plate to better show the contrasting annual rings, sectioned with a low-speed saw or Dremel tool, sanded with a very fine grit, and examined under a microscope. Annual rings are then independently counted by at least two trained observers to confirm the age estimate.

15. Bomb radiocarbon dating is a useful tool in validating earstone annual ring counts. This specific type of carbon-14 dating has been used to confirm age estimates in several species, including bigmouth buffalo and alligator gar. A recent study of 24 alligator gar collected in Texas, Arkansas, and Florida used bomb radiocarbon dating and found the fish to be 26 – 68 years old, with the study’s oldest fish coming from the Escambia River in Florida. (A separate study using otoliths to age alligator gar included a 101-inch fish from Lake Chotard, Mississippi that was 95 years old.)

16. Biologists are looking at nonlethal ways of estimating fish age. In some species, the first pectoral-fin ray can be clipped and the annual growth rings of the ray can be counted similar to how earstone rings are counted. Researchers used this technique in 2016 and 2017 to age nearly 300 blue sucker, a species of greatest conservation need, from Oklahoma’s Red and Kiamichi rivers. The fish were found to be between 6 and 28 years old. Blue suckers are thought to achieve much of their lifetime growth before reaching adulthood; males mature at 3 years of age, while females are thought to mature at 5 years of age.

- MORE THAN JUST WHOPPIN' FISH STORIES

Record-breaking fish give biologists an idea of Oklahoma’s potential.

Image

Oklahoma’s state record alligator gar, snagged by Paul Easley.

17. Oklahoma’s Biggest Fish: Paul Easley snagged and released the state record alligator gar, a 254-pound 12-ounce fish that measured more than 8 feet in length with a 44-inch girth, from Lake Texoma in April 2015.

18. Most suckers have downturned mouths and often aren’t caught on conventional bait and tackle. So Hugh M. Newman’s record-breaking smallmouth buffalo, snagged on an 8-pound test line and a swimbait from Broken Bow Lake in May 2019 was an impressive feat! The female fish weighed 66 pounds 3 ounces and measured 39 and 15/16 inches in length and had a girth of 38 and 11/32 inches. The fish broke the previous Oklahoma smallmouth buffalo record by 22 pounds.

19. The state record spotted gar, and the five previous state records, all were taken by bowfishing. The record has been broken five times in 19 years.

20. Not game, but not light weight either. The two biggest fish on Oklahoma’s angler record books are nongame species. The state record alligator gar tops the list, followed by the 164-pound world-record paddlefish snagged from Keystone Reservoir in June 2021. The top game fish species, a blue catfish in the unrestricted division caught on a jugline from Lake Texoma in 1988, comes in at No. 3 overall with a weight of 118 pounds 8 ounces.

21. Thirteen Oklahoma record fish break the 50-pound mark. Nine of the fish, representing six species, are native nongame species; two of the fish, both blue catfish, are native game fish; and the remaining two fish, both grass carp, are nonnative, invasive fish.

22. Anglers have played an important role in broadening our understanding of Oklahoma’s fish. The Wildlife Department regularly surveys our fish populations, but most often encounters smaller individuals in its nets. By allowing the Wildlife Department to examine record and near-record fish, collect measurements, and even remove otoliths for aging, anglers have helped to show the growth and age potential of our fish communities.

- LET'S TALK STRATEGY

Most fish produce large numbers of eggs to offset egg and larvae predation and death, but species may have different spawning and survival strategies.

Image

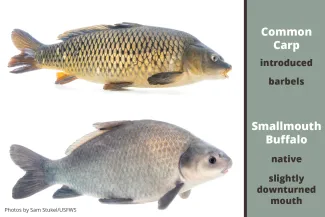

23. In many fish, females grow larger and may mature later than males of the same species. Additionally, older and larger females can produce larger, higher quality eggs and larvae that have a greater chance of survival than smaller females of the same species.

24. A female alligator gar may produce more than 4,000 eggs per kilogram of body weight for a single spawn. For a 50-pound fish, that may be more than 90,500 eggs. For a 100-pound fish, that may be more than 181,000 eggs.

25.Many native, long-lived Oklahoma fish like gar, buffalofishes, and other suckers are well adapted to drought, and their extended lifespan allows them to wait years for conditions to again turn favorable before spawning. When rivers and lakes refill at the end of drought years, vegetation that has since grown on the exposed shorelines and banks is submerged and creates ideal spawning and nursery conditions for these fish.

26. Adult gar have stout scales that serve as body armor to protect them from many potential predators, but their eggs and larvae aren’t so formidable on the outside. Instead, the eggs and larvae rely on a different survival tactic – toxicity. The eggs are toxic to potential predators like mammals (including humans), birds and crayfish. Larval gar maintain the toxicity several days after hatching.

27. Oklahoma’s native fish may be spawning homebodies, broadcasters, or opportunists.

- Flathead catfish dig holes or enlarge natural cavities for their nests and the male guards 100,000-plus eggs for about a week while agitating the eggs with current generated by its fins.

- Redspot chub are another spawning homebody; the fish build 1 – 2 foot tall gravel mounds with their mouths to attract females to spawn. Cardinal shiners and southern redbelly dace later move in and use the chub-created mounds to spawn as well.

- Fertilized shoal chub and prairie chub eggs are broadcast upstream and must float 50 – 100 miles downstream before hatching.

- The jack-of-all-trades award goes to the red shiner, whose adhesive eggs can stick to rocks, wood and other plant matter, along with metal and plastic, which allows the species to reproduce in pretty much any habitat.

28. Bigmouth buffalo eggs are about 1/16 of an inch in diameter. The straw-colored eggs sink among flooded vegetation and hatch within 5 days when water temperatures are 65 degrees, and within 3 days when water temperatures are 75 degrees.

29. When adult and juvenile fish of the same species have different habitat or food needs, the adult fish tend to migrate upstream and spawn where conditions are more favorable for their young before returning to their preferred habitats. The blue sucker, a species of greatest conservation need, has been found to make impressive migrations, but the species isn’t consistent in its migration. Some individuals may migrate more than 180 miles within a year while others may stay within the same 1.8-mile reach of the river. Cool temperatures and high flows trigger the migration.

- WHERE BIOLOGY MEETS THE HUMAN ELEMENT

Managing Oklahoma’s native fishery requires a solid understanding of what the fish need to survive, maintenance of adequate habitat for all life stages, and a well-balanced harvest.

Image

30. The life histories of Oklahoma’s native nongame fishes present different management challenges from their sportfish counterparts. Fish like paddlefish, gar, and buffalofishes have rapid growth in their early years, reach maturity several years after hatching, and can live decades after that. Once these fish reach maturity, their focus shifts from growth to producing the next generation. As a byproduct, “fully grown” fish can encompass a wide range of ages, which requires a different harvest management strategy than short-lived sportfish.

31. Biologists spend many days each year conducting stock assessments to understand where our fish communities stand and to help guide regulations and catch limits. For long-lived species that may not reproduce every year – or go more than a decade without reproducing – strong year classes may be key to the population. Understanding the age demographics and variations in year classes is a crucial factor in proper stock assessments of species like buffalo and gar, whereas biomass may be a bigger factor in stock assessments of other species.

32. Larger fish are more often sought-after by anglers and are typically older females of the species. A careful harvest balance is needed to ensure a healthy sex ratio is maintained and large, old females are allowed to remain in the stock. Research indicates older, larger females can have a disproportionally positive impact on recruitment. One old female can’t simply be replaced by two younger females.

33. When the Wildlife Department surveys our fish communities, we can compare today’s results to “baseline” results collected in previous decades. One of the many historic databases we can lean on to assess the health of Oklahoma’s fish populations was collected in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s by high school science teacher turned Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality ichthyologist Jimmie Pigg. Not only did Pigg collect valuable data on Oklahoma’s fish communities, but he also introduced his students to our diverse fishes and aquatic habitats. His legacy of scientific exchange lives on in his former students, in his archived data sheets and in the 42 articles he authored or co-authored that were published in the “Proceedings of the Oklahoma Academy of Science."

34. A variety of cues can trigger fish to spawn, but for those species tuned-in to seasonal flows, maintaining connectivity within the river network is key. Unnatural flow pulses from dams, like large peaks in discharge followed by a rapid decline, could throw off the timing of fish spawn and lead to a failed reproduction year.

35. Biologists consider the availability of spawning and nursery cover to be one of the most critical variables that can affect the early life of alligator gar. Manipulating water levels so that vegetation is allowed to grow along the edges and then flooded for at least five days can provide quality spawning habitat.

36. To give the declining population of alligator gar a boost, the Wildlife Department partnered with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to produce alligator gar in a hatchery. Nearly 34,000 1.8-inch fingerlings were stocked into flooded vegetation where Lake Texoma meets the Red River in 2017. Annual survival of those fingerlings is estimated at about 83%.

- NOT ALL “CARP” ARE CARP – A CASE OF MISTAKEN IDENTITY

Oklahoma’s waters have been invaded by several invasive fish. Unfortunately, large-bodied native nongame fish may be lumped in with, or mistaken for, nonnative invasive carp. Especially when viewed in water, from above.

Image

37. Oklahoma’s native fish, and the biologists that manage our fisheries, are contending with several nonnative, aquatic nuisance species that aggressively compete with our native communities for resources. These invasive species may have been brought to Oklahoma’s water intentionally or accidentally.

38. Common carp, the carp species most similar in appearance to native buffalofishes, quillback, and other large sucker fish, were introduced in the United States sometime after 1831 and were first reported in Oklahoma in 1882. The presence of barbels, or whiskers, at the corner of the mouth can be used to distinguish this invasive carp from native sucker fishes.

39. Bighead and silver carp were first brought to the United States in 1973 by a private fish farmer in Arkansas. Natural disasters like flooding have allowed the “jumping fish” to escape from fish farms and spread into at least 23 states. Bighead carp were first documented in Oklahoma in 1992; silver carp were first reported in the state in 2012.

40. Invasive carp have overtaken many Mississippi River drainage waterways and have completely altered some native fish communities. A recent study in the Upper Mississippi River System showed silver carp competed with young sportfish for zooplankton, leading to reduced recruitment of the native fish. Another study in Illinois showed the body condition of gizzard shad and bigmouth buffalo had significantly declined after the establishment of bighead and silver carp.

41. The Wildlife Department produces 10 – 15 million fish in hatchery ponds to be stocked in public waters each year. To ensure only clean and healthy fish are stocked, hatchery staff inspect the fish for various hazards, including aquatic nuisance species. Fisheries staff also clean, drain and dry boats and sampling gear to prevent the spread of invasive species across the state. These measures also can be followed at a local level; before stocking, ask your fish supplier what steps they've taken to keep nonnative fishes from spreading further into Oklahoma, and clean, drain and dry your equipment after a boating or fishing excursion.

42. While nonnative carp have been the most harmful to our native fish communities, dumped aquarium fish and plants also can create unnecessary challenges. Rehome unwanted pets and plants or dispose of them properly.

43. The common carp and grass carp occur in waters across the state, but many Oklahoma waterways are still free of bighead and silver carps. To keep those fish from spreading, bait fish collected from infested waters cannot be moved to another lake or river. More regulations geared to protecting Oklahoma’s waterways from aquatic nuisance species can be found in the Oklahoma Hunting & Fishing Regulations.

44. Anglers can help protect Oklahoma’s waterways from invasive carp by not releasing carp back into the water, and reporting bighead and silver carp catches to the Wildlife Department at (918) 683-1031. Sharing the location of the carp, number of fish observed, date of observation and a photograph can help the Wildlife Department track these invasive fish. The Wildlife Department also may be able to collect biological data on your carp.

- GONE FISHIN’

Swapping fish stories can help build awareness of our amazing fish communities … and going fishing can help the Wildlife Department learn more about Oklahoma's ecologically and economically valuable fishery.

Image

45. Your catch can be proudly shared on a variety of platforms, including The Dock! There, the Wildlife Department showcases any fish species caught in Oklahoma, no matter the size or method of take. Uploading your photos is a great way to build awareness of our fish communities, and may encourage others to enjoy Outdoor Oklahoma.

46. Buffalofishes have a long-standing role in the history of fishing in North America and Oklahoma. William Clark journaled about catching a buffalofish in Nebraska along the Platte River in July 1804 while on the Lewis and Clark Expedition. In Oklahoma, the native fish were commercially harvested from the 1930s to the mid-1980s. Records are limited, but buffalofishes are thought to have made about 44% of the annual harvest from Oklahoma reservoirs from 1957-1969, with annual hauls of buffalofishes weighing nearly 300,000 pounds.

47. In Oklahoma, nongame fish can be taken by bow and arrow, also known as bowfishing. This technique has a long history, with evidence of bowfishing coming from archaeological sites, illustrations and in early writings. While participation in archery at large dropped in the early 20th century and the sport became “nearly a lost art,” innovations like the compound bow in 1966 have revitalized the method of take and have opened bowfishing opportunities for those unable or uncomfortable handling longbows or recurve bows.

48. Alligator gar have a closed season from May 1 through May 31 to protect spawning fish. Throughout the rest of the year, harvest must be reported to the Wildlife Department within 24 hours by e-check through Go Outdoors Oklahoma.

49. Fishing can provide a tasty meal, a great mental health break, or simply a reason to get outside and explore Outdoor Oklahoma. More than 250,000 annual resident and nonresident Oklahoma fishing licenses were sold in 2020.

50. The Wildlife Department can turn a $25 fishing license into $100 of conservation. Both hunting and fishing license dollars unlock a pool of federal funding collected from excise taxes on hunting and fishing equipment and returned to the states at a 3:1 match. Sport Fish Restoration Program grants can help create or maintain fish habitat, improve angler access, and fund diet and population studies of our fish.

From popular lakes to secret fishing holes, public docks to private ponds, and boat ramps to shorelines, anglers have been hitting Oklahoma's waters and are sharing amazing photos of their catch on The Dock. Each snapshot shares the story of our state’s rich fishery, but mostly from the viewpoint above the water line.