For many duck hunters, the tail end of winter marks the time of year when waders, decoys and other gear will go back into storage. But for wetland managers, the end of one season simply marks the start of the next.

“There’s not much of an off-season in wetland management,” said David Banta, Wildlife Technician at the Wildlife Department’s Love Valley Wildlife Management Area near Thackerville.

The ducks — and the duck hunters — attracted to the area’s Wetland Development Units are the result of six months or more of muddy boots, scheduled flooding events and drawdowns, unpredictable rainfall and flooding, plant identification and management, and much more.

A duck hunter's perspective may vary from a wetland manager's, but the goal and end results can closely align.

“I have to look at the wetland units with a different eye than the average duck hunter,” Banta said. “When duck hunters wade out on opening morning to set their decoys, they’re focused on the birds they may see. The vegetation we’ve spent the entire growing season managing has died back and is mostly underwater and out of sight. But it’s still playing a vital role in their hunt.”

A wetland unit’s plant community can provide ducks and other birds with three fundamental components in the winter: structure to loaf in and hide behind; food in the form of ripened seeds; and when the standing vegetation is mowed and flooded, food in the form of invertebrates that feed on the flooded vegetation.

In order to have that structure and food available during next year’s duck season, Banta and many other wetland managers begin scheduling slow late-winter water drawdowns that will expose mudflats and encourage the germination of beneficial flowering plants such as annual smartweeds and beggarticks in the early spring.

Water control structures allow wetland managers to quickly flood or drain a unit to achieve the desired plant response.

The timing of these drawdowns can create different plant responses; earlier drawdowns can trigger the germination of more flowering plants, while later drawdowns can trigger the germination of more wetland grasses that also produce a high volume of beneficial seeds.

The “right” timing can vary across regions of the state, the manager’s plant preferences, and even with the current year’s weather conditions.

For Banta, the ability to control the timing and duration of the water drawdowns is key to the potential success of most wetland units.

“Natural drawdowns are a viable option; it’s a slow process which allows for a longer period of moist soil conditions that are often ripe for germination, but you are left completely at the mercy of Mother Nature. A heavy early summer rain, for example, could stunt or kill a stand of great wetland plants you’ve worked hard to establish, if the water isn’t diverted off of the unit in short time.

“But investing in at least one water control structure can give wetland managers the upper hand by not only allowing them to control the timing and duration of drawdowns, but also maintaining the unit’s progress for the upcoming duck season.

“Controlling the timing and duration of the water drawdown can open so many doors for a wetland manager. From my perspective, a manager who can time and control drawdowns is 100 steps ahead of a manager who can’t.”

Beyond recognizing when to add and remove water to trigger desired plant responses that produce duck food for the upcoming hunting season, Banta is also thinking about and managing a layer deeper: the wetland unit’s seed bank.

“Each wetland unit comes with its own set of challenges. Here at Love Valley, we can make strides toward a desirable wetland plant community, but the units are ultimately at the mercy of the Red River.”

Much of Love Valley WMA, including the Stevens Spring Wetland Development Unit, is within a quarter-mile of the Red River. Heavy rainfall can occasionally cause the river to rise and get out of its banks and into the wetland units — sometimes for prolonged periods.

“The river, and our proximity to it, has created really fertile soils in our wetland units, which is a huge benefit. But when the river gets out of its banks for extended periods, it can bury desirable seed under a layer of silt. In addition to burying the good seed too deep to germinate, flooding from the river can also deposit less desirable seeds. But if we can get three to four years of desirable seed production using moist soil management, we typically have a high enough density of desirable plants in the seed bank that they can outcompete the less desirable.”

Although periodically covered by river silt during flooding events, the desirable seeds are still there deep in the seed bank. By disturbing the unit’s soil by disking after it dries sufficiently, a manager can actually retrieve and re-establish the hard-earned seed bank by redepositing them back in the germination zone, depth-wise.

Periodic mechanical soil disturbance also provides an additional benefit. It sets back plant succession, favoring a plant community of annual grasses and weeds that produce high volumes of nutritious seeds beneficial to migrating waterfowl, as opposed to far less desirable perennial plant communities that gradually become naturally established over time without soil disturbance.

When managing the seed bank, knowledge is power. Many native wetland plants can pull double-duty in a wetland and provide both seeds and vegetation mats for invertebrate cover. But many plants – both desirable and undesirable – look very similar when they first germinate. Banta has had to learn how to correctly identify freshly germinated plants and act quickly if undesirable plants start sprouting.

Distinguishing valuable wetland plants like barnyardgrass, sedges and careless weed when the plants are less than three inches tall can give wetland managers a head start against more undesirable plants.

“Knowing which plants provide nutritious seeds for ducks and other wildlife, and which plants dominate your units as they mature, is important. But knowing which plants are sprouting while they are still small seedlings is vital. It gives you a management leg up and may let you get ahead of the undesirable plants with early control measures.”

Wetland Look-Alikes: Desirable and Undesirable Plant Combos

By late spring, wetland units generally have an established plant community and are well on their way to producing food and cover for duck hunting season. But Banta regularly checks in as the growing season progresses to see how the units are faring and if any less-desirable plants have germinated since his last visit. During a recent check-in, he pointed out two sets of wetland look-alikes, each with a desirable and undesirable plant combination.

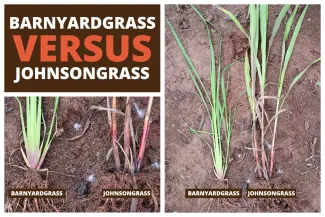

Banta’s favorite wetland plant, barnyardgrass, produces a lot of high energy seeds — one healthy plant can produce 750,000 to 1 million seeds — and provides a really stout mat of vegetation for invertebrates. But the plant can be easily misidentified for the less desirable johnsongrass, a nonnative plant that can provide some supplemental seed for ducks and vegetation cover for invertebrates. Johnsongrass tends to become a monoculture, outcompeting other desirable plants and greatly decreasing plant community diversity.

To distinguish the two grasses, Banta focuses on the base of the stems. Barnyardgrass has flattened stems and a light purple coloration at the base of the stem.

Johnsongrass has rounded, darker red stems. As johnsongrass matures, it also develops a bright midline vein down the center of its leaves.

“I don’t actively manage for johnsongrass in the units. I’d much prefer barnyardgrass or a native plant to be growing. But johnsongrass can provide ducks with some seed and invertebrate cover, so it’s a decent Plan B if all else fails.”

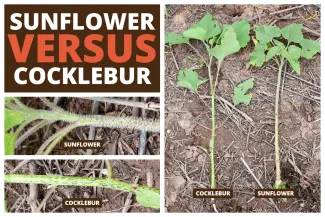

Another common set of wetland look-alikes is annual sunflower and Banta’s wetland enemy No. 1: rough cocklebur. When the plants first sprout, the initial leaves of both species are long and narrow. But while the sunflower’s initial pair of leaves are rounded at the end, the cocklebur’s leaves are more pointed. As the plants grow, the incoming leaves are both heart-shaped, but other differences can be more readily seen. The sunflower has extremely rough “hairy” stems, while the cocklebur has more smooth stems with purple streaking or spotting.

“As frustrating as cocklebur can be, the plant’s life strategy is truly fantastic,” Banta said. “It’s an annual plant, but each ‘bur’ has two seeds. The larger seed typically germinates the year it was produced. But the smaller seed can germinate later in the season it was produced, or in the following year. That means we may have to fight the same crop of cocklebur, an annual plant, for at least two years. In fact, some studies suggest that their seeds can remain viable for up to 5 years, making it a very challenging adversary.”

Being able to recognize the tiny pointed leaves of newly germinated cockleburs allows Banta to take steps to control the less-desirable plant, through herbicide or shallow flooding, before it takes hold and dominates the wetland.

A rough cocklebur plant can look similar to an annual sunflower plant. Pointed leaves of recently germinated plants (upper left), a unique seed (lower left) and relatively smooth stems can help wetland managers distinguish the two native species.

Boots-on-the-ground experience has been Banta’s best teacher for early plant identification, but he’s also leaned on other wetland managers and wetland management guides from the Natural Resource Conservation Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to better recognize and manage Love Valley WMA’s plant communities. Begin gathering your wetland resource library or reach out to the Wildlife Department for an in-person visit with a biologist to better understand your wetland.