An ancient art is the focus of a modern science experiment, as researchers recently teamed up with bowfishing anglers for a unique bowfishing tournament and learning opportunity at Shell Lake in northeast Oklahoma. As part of a joint effort between the Wildlife Department and Oklahoma Fish Stickers, a simulated bowfishing tournament was held Aug. 9-10 that gave insights into the sport, its targeted fish, and how the two groups can maintain both the long-lived fishery and the specialized pursuit of fish.

“We’re seizing any opportunity we can to learn more,” said Jason Schooley, a senior fisheries biologist with the Wildlife Department. “This tournament gives us a unique opportunity to describe the population level impacts of bowfishing at Shell Lake, but the work complements other ongoing efforts, including a multi-year genetics project.”

Bowfishing Basics

A combination of archery and fishing, bowfishing typically involves a hunting bow that has been modified to include a reel with line that is attached to an arrow.

Humans have long caught fish using a bow and arrow, with evidence from archaeological sites, and in early written accounts, reports, and illustrations. The sport has since become more accessible with the invention of the compound bow in the 1960s and availability of customized boats with raised decks and lighting systems for night fishing. Bowfishing is now thought to be one of the fastest growing segments of archery in the United States. Today, bows and crossbows can be used to take nongame fish in Oklahoma. Arrows used for bowfishing must have one point, two or more barbs, and be attached to the bow by a line for retrieving fish. More information can be found in Oklahoma’s fishing regulations.

The Shell Lake Experiment

🎥 Click to watch as Oklahoma Fish Stickers participate in a simulated bowfishing tournament with tagged fish and biologists learn about the sport and its targeted fish.

To study the potential impacts of bowfishing on nongame fish, Wildlife Department biologists first coordinated with the City of Sand Springs to turn Shell Lake, a source of drinking water for the Tulsa suburb, into a temporary study site. The 573-acre reservoir, normally closed to both bowfishing and nighttime use, is large enough to mimic a tournament setting but small enough to limit several outside variables. The city issued a special permit and agreed to open the lake to accommodate the nighttime bowfishing study.

The lake was then visited in late June and early July to study the fish populations. Biologists used an electrofishing boat to momentarily stun and capture the lake’s native nongame species like smallmouth buffalo, spotted gar, river carpsucker, and freshwater drum.

“There are no standardized methods for electrofishing these species, so we were modifying techniques on the fly,” Schooley said. “Many of the fish could feel the electrical field from a distance and would zip past. We learned to herd them into the field and essentially ambush the fish to catch them.”

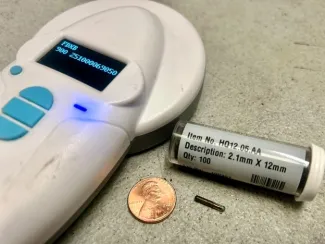

Despite their early struggles surveying Shell Lake’s fishes, the team’s catch rate improved each day. The survey ended once more than 900 fish, mostly native nongame species, were caught. A microchip, similar to those used to identify pets, was injected into each of the study’s gar and buffalofishes before they were returned to the water, allowing biologists to estimate the total number of fish in the lake, and later estimate the percentage of fish harvested.

Similar to the microchips used by veterinarians to identify pets, PIT tags (or Passive Integrated Transponders) are often used in fish and wildlife studies to identify individual animals. The tag has no battery but is activated by a signal emitted by the handheld scanner, causing the tag to respond with a code unique to that fish, which is shown on the display. This same technology is used by Pikepass to identify vehicles driving on Oklahoma turnpikes. In long-term studies, individual fish growth and movements can be accurately tracked using these tags.

Biologists then invited five teams from Oklahoma Fish Stickers to fish each tournament night, with up to four members per team. The event resembled other fishing competitions: teams stayed within the tournament boundaries, followed state fishing regulations, and for this tournament, delivered all fish shot to the weigh-in with no culling allowed.

After launching their boats, team members attended a brief pre-tournament meeting and set out at 8:30 p.m. They fished into the night and returned to the dock at 1 a.m. with their barrels of fish. As soon as the boats were trailered, each team queued at the weigh-in station to learn the tournament results.

Weigh-In Winners

After two nights of fishing, the tournament’s 10 teams hauled in a collective 1,770.64 pounds of fish, heavily dominated by smallmouth buffalo and spotted gar. Each team’s catch was weighed and individual fish were scanned for tags as soon as the boats left the water, with nightly prizes for the top two teams with the greatest total combined weights and for the individual participant with the heaviest single fish shot.

Team T-N-T, based in Coweta, claimed the top prizes the first night, with 334.2 total pounds of fish, including a 19.84-pound black buffalo. The second night’s catch was led by Lynch Mob II, with 175.04 total pounds of fish caught, and Team Rousey’s 10.58-pound smallmouth buffalo.

Tournament sponsors included the Oklahoma Wildlife Conservation Foundation, the Oklahoma Chapter of American Fisheries Society, Bass Pro Shops® Broken Arrow, and Tulsa Scheels.

Post-tourney Data Collection

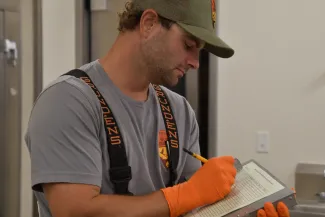

Once the prizes were handed out, each night’s fish were hauled to the Wildlife Department’s Miami office in team-specific barrels and were stored in a refrigerated locker. The following Monday, biologists met to learn as much as they could from the tournament fish. Each fish was given an identification number and visited five stations, getting scanned for tags, weighed and measured, and dissected along the way.

Fisheries technician Matt Pallett collected data about each fish, including its weight, standard measurements, and sex, along with the number of each species of fish harvested. These data will help biologists better understand the potential impacts of bowfishing on the native nongame fish population.

“We’re collecting everything we can,” said Schooley. “We’re looking at the length, weight, sex, and age of each fish to learn more about the age and size structure in the population and how it compares to other lakes. And we’re taking tissues for other collaborators to learn more about the genetic structure of the lake.”

By the end of the long day, the tournament’s 325 fish had been processed, generating possibly the first ever dataset on bowfishing specifically designed to evaluate the impacts of the sport and its take on native nongame fishes. Why hasn’t this been done before? Well, it’s a matter of scale. Oklahoma bowfishing tournaments are generally held on larger reservoirs. To get adequately detailed information on nongame fishes from a large reservoir requires a massive amount of time and effort – which has not been a focus for managers in Oklahoma or other states. Shell Lake provided the right-sized venue for this focused study. Though the lake is considered small, the dataset is substantial and the age structure, morphology, population modeling, and genetic analyses are ongoing. Preliminary estimates of pre-tournament population sizes were approximately 3,000 for buffalofishes – smallmouth buffalo, bigmouth buffalo, and black buffalo, combined – and 1,200 for spotted gar. With these estimates of population size and the known numbers of these fishes taken in the tournament, biologists can have a pretty good sense of the direct harvest impacts of the experimental tournament and develop population models to determine what is sustainable. Biologists hope to complete a report on the study by early 2025.

Once all samples and measurements were taken and data had been collected from the tournament fish, biologists hauled the fish carcasses to a facility in Missouri where they were salvaged into pet food.

While the Shell Lake tournament provided a unique experiment for biologists, it’s not the first attempt to learn more about Oklahoma’s native nongame fish and how to best manage the sport of bowfishing in the state. In 2018, the Wildlife Department partnered with sponsors of the Bass Pro® U.S. Open Bowfishing Championship, held that year in Broken Arrow, to collect information on the harvested fish and survey the participating teams. A case study of the event was published in 2020 along with a history of the sport, survey results and summarization of each state’s management strategies, and a framework for understanding and proactively managing bowfishing. In 2021 and 2022, biologists conducted trials to better identify the mortality rate of fish that have been shot and released. And in 2023, the Wildlife Department expanded its statewide fisheries management plan to include native nongame fishes like buffalofishes and gars with a goal of providing for a sustainable recreational fishery. As part of that goal, biologists have followed eight of Oklahoma Fish Stickers’ tournaments in 2024. Similar to the Shell Lake tournament’s catch, fish were collected after each tournament along with data about the individual fish. All told, the Wildlife Department handled more than 5,000 fish totaling more than 20,000 pounds from bowfishing tournaments in 2024.

Mitchell Herron, an Oklahoma Fish Stickers member and Shell Lake tournament participant, summed up the partnership.

“We want to work together to see what we can figure out.”

This commitment to cooperation and collaboration echoes multiple sentiments voiced by bowfishers who spoke at the January 2024 Oklahoma Wildlife Commission meeting, where some rule changes for nongame fishes and bowfishing were under consideration.

“Ultimately, if you really wanted to help the native fish species, do the population studies, let’s figure out what they can support, let’s set up a program, work with the bowfishers, work with the giggers, let’s come together and let’s figure out a way to utilize these fish in a better way.”

-Peter Gregoire, then president of the Bowfishing Association of America

“I just hope y’all do it right and do the scientific data on this first before you do any of those limits.”

-Randy Woodward, Bowfishing Association of America Hall of Fame

“Please do the science first and get the data and show us that, you know ‘hey these are the populations, let’s monitor them for two years and then we’ll come back, meet again. We’ll all talk again,’ hopefully, and, you know, then we’ll have some sort of better understanding.”

-Steven Whitney, Bowfishing Association State Representative for Missouri

Oklahoma’s efforts to better understand bowfishing and native nongame fisheries management may sound novel, but they are part of a larger movement nationwide. On the heels of multiple studies demonstrating the conservation value of native nongame fishes, such as buffalofishes and gars, state managers nationwide are taking a more critical look at populations and the fisheries that target them. With a greater knowledge of Oklahoma’s native nongame fish and the fishing methods that target them, the Wildlife Department hopes to play a more effective role in managing these resources sustainably.

Curious about Oklahoma’s nongame fish? We fished through several resources to find the story swimming below the surface and hauled in 50 fish factoids about the lives of Oklahoma’s incredibly diverse native nongame fish. Dive into Oklahoma’s fishes to learn about their various survival strategies, mind-boggling records, how biologists balance the fishery, and how anglers have pitched in to help showcase the potential of Oklahoma’s populations.