Biologists are using an airboat to cruise two Oklahoma rivers as they check in on nesting interior least terns. The small fish-eating birds return to Oklahoma’s sandy river systems in late spring and form nesting colonies on exposed sandbars. The flat-bottomed boat, powered by a powerful engine and propeller, allows biologists to traverse long stretches of the shallow Arkansas and Red rivers as they make their counts of the endangered birds.

“This will be our first run of the summer.”

Tonya Dunn, biologist with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers stands next to a large airboat as she makes final launch preparations for the day-long survey of nesting interior least terns.

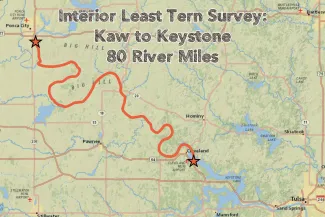

The USACE Tulsa District has been monitoring nesting terns in Oklahoma since the late 1990s, and Dunn has been a member of the survey team for the last 12 years. She and fellow biologist Tony Clyde, Ph.D., will use the flat-bottomed boat to crisscross a little more than 80 river miles of the sandy and oftentimes shallow Arkansas River, from boat ramps near Ponca City and Kaw Lake south to Cleveland and Keystone Lake. The duo will make more than 15 stops along the way, searching for nesting activity where terns have formed colonies in the past, and looking for evidence of new colonies.

“Terns often return to the same general area each year to nest on exposed sandbars,” Dunn said. “Even though we’ve marked those known locations with our GPS, we don’t yet know if the birds are using those sandbars this season, or if they’ve shifted their colony up or downriver.”

“Our goal for today’s survey is to get an idea of the tern population on this stretch of the river – how many adults are present and how many potential nests may be under way,” Dunn said. “We’re also checking the sandbars of active colonies to see how much clearance, or freeboard, the nests have from the current water level.”

As Dunn and Clyde arrive at the first known colony, several birds lift from the sand and begin swift flights across the wide sandbar. After the initial disturbance from the boat’s arrival, the birds settle back on the ground and give the survey team a chance to observe their behavior. None of the adults remain on the sand long enough to indicate they’re incubating eggs, so Clyde records the count of adult birds and Dunn fires the engine back up and navigates to the next survey stop.

A foraging adult tern making dramatic dives for fish into the river from a midair hover signals their arrival at another colony about 10 minutes downriver. The boat slows and is temporarily docked on the bank of the survey’s second tern colony.

Dunn and Clyde climb to the boat’s highest perch and count the adults flying overhead. As the birds settle back on the ground, the duo scans the sandbar with binoculars and begins calling out the number of nesting terns they see.

“Terns make shallow scrapes with their body and lay their eggs directly on the sand,” Dunn said. “Fortunately for us, they often nest next to a small stick or other landmark on the sandbar. Otherwise it would be difficult to describe the nest location to each other for confirmation.”

For Dunn, a telltale sign a tern is incubating eggs is in the way it sits on the sandbar. “A lot of times they’ll be sitting in a small crater and the tail will be sticking out.”

After getting her bearings, Dunn steps onto the sandbar and makes a quick but careful walk to the closest nest. There she finds three small, well-camouflaged eggs next to a weathered stick.

“We only check the status of a few nests during the entire survey,” Dunn said. “Terns typically lay three eggs and incubate those eggs for about three weeks. Since this nest is likely complete, we’ll know to watch for chicks the next time we survey this stretch of the river.”

Back on the airboat, Dunn and Clyde continue their downriver survey, counting adult birds and potential nests along the way. Twenty miles from a boat ramp near Keystone Lake, they pull up to their last known tern colony.

“Oh, this is a good site,” Dunn said. “I have seven nesting birds in my field of view right now.”

The final site’s 33 adults and 22 nests bring the day’s survey total to 176 adult terns, and at least 63 nests.

“This is what we like to see.”