Oklahoma is known for its incredible natural diversity; our state is often lauded for having everything from pronghorn and vast prairies in the northwest to alligators and forested swamps in the southeast. And while many factors contribute to this diversity, there’s no doubt the variety of environmental conditions experienced across the state plays an important role.

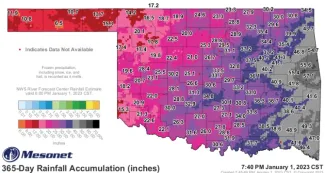

The Oklahoma Mesonet maintains a network of 120 environmental monitoring stations across the state that collect a variety of weather-related data, including rainfall accumulation, every five minutes. This map shows the 365-day rainfall accumulation from January 1, 2022, to January 1, 2023.

In 2022, the Oklahoma Mesonet recorded a 128-degree temperature variation between the coldest (-12° on Feb. 4 in Kenton) and warmest (115° on July 19 in Mangum) days; a temperature reading of at least 103° across all stations (also on July 19); as well as a 51.8-inch difference in annual rainfall among its 120 collection sites.

We visited with biologists at Wildlife Management Areas near Mesonet stations receiving the lowest and highest rainfall amounts in 2022 to learn how the Wildlife Department meets its habitat management goals and adapts to wildly different conditions.

The View from Oklahoma’s Driest Site

2022 Total Rainfall Logged at the Goodwell Mesonet Station: 6.48 inches

Normal Annual Precipitation for Texas County: 19.29 inches

“The Panhandle may be one of the driest regions of the state, but it provides a lot of unique hunting opportunities that you just can’t find anywhere else in Oklahoma.”

Biologist Hayden Savage manages the Wildlife Department’s five western-most public lands, spanning from his home near Beaver River WMA to Rita Blanca WMA, located 140 miles west near Felt. The three-county Panhandle region often experiences dry conditions, but 2022 was its fourth driest on record since 1921. The Mesonet station closest to Beaver River WMA logged 13.71 inches of rain in 2022 while the Goodwell Mesonet station – located at the midpoint of Savage’s range and within 30 miles of three of his five designated WMAs – only observed 6.48 total inches of rain.

“Our low annual precipitation definitely shapes a variety of our management goals in the Panhandle,” Savage said. “One obvious issue we have is the lack of natural water sources for wildlife. To help with that, we’ve installed more than 50 water sources across the five Panhandle WMAs, varying from solar wells, windmills, and guzzlers.”

Pronghorn, a keystone of Oklahoma’s natural diversity, can be found throughout Oklahoma’s Panhandle. There are only three Wildlife Management Areas where this species may be found with mule deer, white-tailed deer, and elk. Photo by Kathy Floyd/RPS 2019.

The Panhandle’s ongoing drought has created a few management challenges for Savage’s team but may also be lending a helping hand by slowing the spread of an invasive species, the nonnative Tamarix, known by many as salt cedar.

Salt cedar has taken hold along several western Oklahoma waterways, soaking up untold gallons of water each year. At Beaver River WMA, the namesake river has even stopped flowing in some stretches that have been affected by wildfires and overwhelmed by the invasive tree.

“Brush encroachment management, including that of salt cedar, is one of our top priorities. We’ve been able to extract trees and their roots from about a mile stretch of the river and have seen the water table rise enough that water is flowing again.”

Despite the nominal rainfall and invasion of the water-guzzling salt cedar, three Panhandle WMAs, Schultz, Optima, and Rita Blanca, still reach a unique diversity milestone: they’re the only WMAs in the state where mule deer, white-tailed deer, pronghorn, and elk may be found on one management area.

The View from Oklahoma’s Rainiest Site

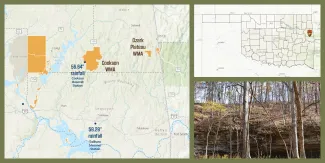

2022 Total Rainfall Logged at the Sallisaw Mesonet Station: 58.28 inches

Normal Annual Precipitation for Sequoyah County: 48.53 inches

Nearly 400 miles east of Savage, biologist Curt Allen manages habitat from the opposite end of Oklahoma’s rainfall spectrum. The Sallisaw Mesonet Station, located about 20 miles south of Allen’s home at Cookson WMA, recorded 58.28 inches of rain, almost nine times the amount observed at the Panhandle’s Goodwell station. The Cookson Mesonet station, conveniently located 100 yards behind Allen’s headquarters, logged the state’s second highest annual rainfall of 2022: 56.64 inches. Similar to Savage, Allen manages five public lands and relies on data provided by multiple Oklahoma Mesonet stations when planning habitat work.

“Our high annual precipitation means that if a seed hits the ground, it’s most likely going to sprout. That’s great when you’re planting a food plot, but not so great when you’re trying to eliminate an invasive species or reduce the number of woody species blocking sunlight from the forest floor,” Allen said.

Eastern Oklahoma and the Ozark Mountain region receive enough moisture to support a diverse salamander community. The dark-sided salamander is just one of 11 species known to occur at Cookson WMA. The drier Panhandle region supports one salamander species, the barred tiger salamander.

Even though Allen works in a two-county area that received higher than normal rainfall this year, the region also experienced a relatively dry summer and fall. The dry conditions temporarily delayed some of the food plots on Cookson WMA, but also created opportunities for Allen’s team.

“We were able to tackle a few projects that we just weren’t able to do over the last two years because of such frequent rain events. We were able to do a few growing season burns this year and worked over some WMA roads.”

Just as low annual rainfall helps shape the Panhandle’s natural diversity, high annual rainfall also shapes the diversity found in the Ozarks.

“The Ozarks, and Cookson WMA in particular, are so much more than just a good place to go hunting. It has wonderful plant and animal diversity and beautiful scenery to discover over every hill.”

Drastically Different Habitats, Surprisingly Similar Management Goals and Techniques

Despite being stationed on opposite sides of the state, with wildly different annual rainfall totals and the resulting differences in prairie and forested habitats, Savage and Allen share primary goals for their respective WMAs.

“We’re both working to maintain quality habitat and forage for a variety of wildlife species,” Allen said. “We’re here to provide area users with good wildlife populations, good access, and great experiences.”

To meet their upland habitat goals, Savage, Allen, and dozens of other WMA managers focus on offering a rich diversity of grasses and forbs, which often means limiting the growth of ever-dominant shrubs and trees.

Regardless of if a plant community is situated in a prairie or in a forest, that plant community is in a continual state of flux. Without natural influences like fire or grazing (historically by bison, now mimicked by cattle), woody plants will eventually invade and become the prevailing species. This plant coup may take multiple decades in the state’s driest ecoregions but may only require 5 – 10 years in the rainiest ecoregions.

“With as little precipitation as we’ve had in the Panhandle the last few years, it can be difficult for forbs – our primary wildlife food producing plants – to compete with more drought tolerant woody vegetation like sand sagebrush and yucca,” Savage said. “With the drought, we’re definitely seeing sand sagebrush progressing more than grasses and forbs in some pastures.”

“We’re able to use prescribed fire and grazing lease agreements on Beaver River WMA to reduce woody growth encroachment and sustain the diversity of vegetation across the landscape.”

In the Ozarks, Allen is also striving for a balance between grasses, forbs, and woody plants, but with a different plant community and with a few different management strategies. “Most of our eastern WMAs have too much timber and not enough grass to support a grazing lease. So, we use other strategies to stay on top of woody plant succession – mowing forest openings, mulching woody saplings, hay leases, and our biggest operation – our prescribed burns.”

The Wildlife Department applies prescribed fire across tens of thousands of acres each year to achieve a variety of management goals, including limiting woody plant encroachment in upland habitats. Factors like humidity, wind speed and direction, and the amount of moisture found in the grasses, litter, and deadfall that fuel the fire strongly influence the success of individual burns and are all measured by the Oklahoma Mesonet. The Mesonet even maintains a separate dashboard, OK-FIRE, to help managers and landowners plan prescribed fire efforts and monitor conditions on the day of the burn.

Savage and Allen agree the real-time local weather data is a game changer for their prescribed burn programs.

“I check the Mesonet app multiple times a day,” Allen said. “And it’s hard to express how beneficial those data are when we’re planning or conducting a burn. With Mesonet and OK-FIRE, we can easily check the dead fuel moisture level forecast to see if it will be a good day to burn. If there’s too much moisture in the leaf litter or fallen limbs, the fire either won’t carry or won’t be intense enough to kill the living woody stems we’re trying to manage.”

Savage also relies on the Mesonet on burn day but is more focused on other readings. “We typically have a high enough fine fuel load to carry the fire but need to closely monitor the relative humidity and wind speeds to make sure we’re within our prescription.”

Savage and Allen may be managing at opposite ends of Oklahoma’s rainfall spectrum, from opposite sides of the state, and in opposite habitat types, but they’re both focused on providing the best habitat for the benefit of Oklahoma’s wildlife, and wildlife enthusiasts.

Savage said, “I think it will shock a lot of people to learn how similar our goals and management strategies are even though we’re 400 miles apart.”

Stay connected to your local conditions by visiting mesonet.org or downloading the app for Apple and Android devises. The Mesonet also offers several OK-FIRE trainings and learning tools.