“It doesn’t look like you’re here to fish.”

Priscilla Crawford, conservation biologist with the Oklahoma Biological Survey, heard that observation multiple times from 2016 to 2021 as she made her way to every Oklahoma public lake’s boat ramp. Instead of carrying the fishing pole and tackle box familiar to many lake-goers, Crawford carried a clipboard, two rake heads attached to each other and a rope, and other gear needed to search for and collect aquatic invasive plants.

“I really enjoyed traveling across the state and seeing all of these lakes,” Crawford said. “Everything from giants like Eufaula Lake to some of the smallest like the Wildlife Department’s Schooler Lake. And it was always fun to visit with the people who saw the clipboard and stopped to talk.”

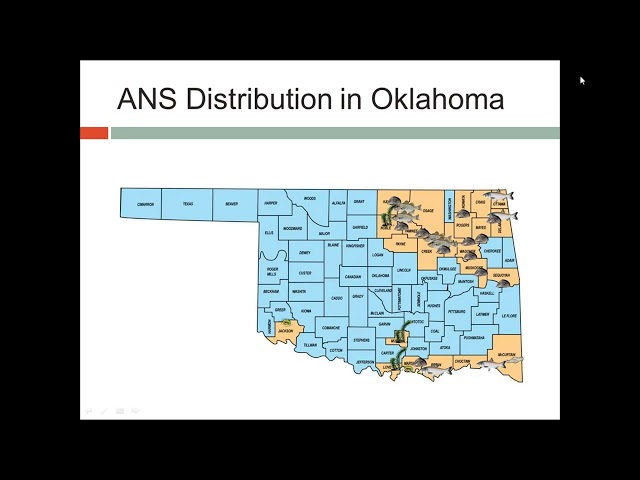

Crawford’s rake- and clipboard-carrying team trekked to 147 lakes and visually inspected more than 500 public access points for aquatic invasive plants. While some of the project’s 16 target plants were well-established and have been recorded in Oklahoma since the late 1940s, other plants have only a two-year history in the state.

“Invasive plants can really affect the users of the lake, whether they’re fishing, swimming, or recreating in other ways. These plants can make the visit not pleasant and also affect users that rely on the lake for drinking water. When the plants start affecting infrastructure, it can cause big problems.

“These lakes are man-made – they’re artificial systems – so it’s not surprising that we find invasive plants in them. But the plants can spread from these artificial systems into nearby natural systems and affect native plant and animal communities that thrive in the riparian areas and further up or downstream of the lake. From an ecological view, that’s why it’s so important to keep these plants out of the lakes or to monitor their presence if they are introduced.”

Finding Invasive Plants...and Some Surprising Good News

After arriving at each lake, Crawford’s team would scan the shore 50 meters on each side of the access point for submerged aquatic vegetation. When plants were spotted, the modified rake was deployed, and a snagged plant sample would be towed to shore by rope. If the sample was identified as an invasive species, a photo was taken, and the sample was collected for the Robert Bebb Herbarium. Environmental conditions, including water temperature and turbidity were also collected at each location.

“We found invasive plants at 45 access points on 25 lakes,” Crawford said. “That’s surprisingly lower than expected, in a really good way.”

As part of the project, Crawford documented each lake’s invasive plant infestations and the potential for each target plant to further invade. While no invasive species is considered “good,” two plants especially concerned the biologist.

“We found alligatorweed all over the McClellan-Kerr navigation system. Because it’s on a commercial navigation channel that gets a lot of traffic, it’s likely this plant will continue to spread.

We also verified a well-known infestation of hydrilla at Lake Murray and documented a new infestation at the nearby Ardmore City Lake. Hydrilla was first reported in the state in 2006 so it’s concerning that it has spread so quickly.”

Alligatorweed can form thick mats that can outcompete native plants, clog waterways, and restrict the oxygen level of water.

Hydrilla may be a popular plant in the aquarium industry but can create dense underwater stands in Oklahoma lakes with stems that can reach 30 feet in length and grow 1 inch in a day.

Eurasian water-milfoil, Oklahoma’s most abundant and widespread aquatic invasive plant, forms dense mats that can restrict light, outcompete native plants, and reduce the oxygen level of the lake.

Despite those troubling findings, Crawford also reported good news.

“Eurasian milfoil was the most common invasive plant for the project – we found it at nearly 10 percent of the surveyed lakes. And while it’s a problem at a few lakes, there’s no indication that it is quickly invading and causing problems at other lakes. It’s been around for more than 60 years, but there were some instances where I checked the lakes it was originally reported in and saw no evidence of it. Granted, we were only looking at public access points but given how these plants spread, you would expect it most at those access points.”

Crawford also observed a correlation between lower infestations and turbid, or muddy, water.

“Most people don’t like turbid water, but it may actually help keep invasive plant species from spreading. If there’s too much turbid material in the water column, these plants may not get enough light to grow and survive.”

Crawford shared more about the survey methods and results in the following recorded webinar.

Join the Fight Against Invasive Species

Aquatic invasive plants are just one category of the more general “Aquatic Nuisance Species” that Oklahoma must battle. Fortunately, actions that help slow the spread of one invasive species or category of species can help slow the spread of others.

“The public plays a huge role in preventing the spread of aquatic nuisance species,” said Katherine Schrag, aquatic nuisance species biologist with the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation. “Properly inspecting, cleaning, draining, and drying your watercraft and equipment like wading boots, tie-off ropes, trailers, and tubes will decrease the chance of spreading aquatic invasives across the state.”

- Clean: Pressure wash any boat, kayak, canoe, or other vessel with hot water (140°F) and remove any plant fragments, mud, and aquatic organisms that are visible. Boots and other gear should also be cleaned after each trip to the water.

- Drain: Drain all water from your boat, motor, bilge, live wells, hauling tanks, coolers, and ballast.

- Dry: If pressure wash is not available, allow the boat, trailer, and equipment to dry thoroughly for at least five days before using in a new water body. If equipment cannot be thoroughly dried, treat with a 10% bleach solution to decontaminate.

Oklahomans can also join the fight by sharing their sightings on the free platforms like iNaturalist or Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System.

“We can run iNaturalist reports every month to see if any new observations have been made,” Crawford said. “Those reports are incredibly helpful and have led to the documentation of new infestations. In some cases, people didn’t realize the flowering plant they took a picture of and reported on iNaturalist was an invasive species.”

Learn more about invasive plants and check out webinars and other ways you can get involved in the fight against invasive plants at okinvasives.org.

Surveys were funded by State Wildlife Grant F15AF01321 and the University of Oklahoma.