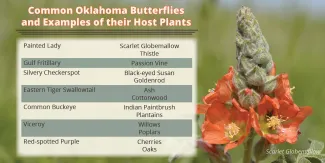

Adding colorful backyard flowering plants, especially host plants, has been a popular way for Oklahomans to help our state’s butterfly community. Luckily, these pollinator-friendly patches can start small – and stay small – while still packing a big win for conservation. But if you’re ready to grow your wildscape, Matt Fullerton, wildlife biologist for the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation, recommends adding plants that benefit the full butterfly life cycle.

“Most adult butterflies can visit a suite of different flowering plants and blooms for nectar. But they’re oftentimes more picky about where they lay their eggs,” Fullerton said. “Adding plants that different butterfly species use as hosts for their caterpillars can turn your backyard butterfly refueling station into a butterfly nursery.”

Female butterflies typically choose suitable host plants by sight and chemical receptors. And while some plants are well-known hosts for a particular butterfly species, most butterflies will use a number of different plant species in the same related family as hosts.

“A lot of people know that monarch caterpillars need milkweed as a host plant, but there are at least 26 species of milkweed plants that grow in Oklahoma, and Monarchs will lay eggs on multiple species of these milkweeds.”

Find more information about butterflies and their preferred host plants in resources like Butterflies and Moths of North America, Butterflies of Oklahoma, Kansas and North Texas, and the Wildlife Department’s Landscaping for Wildlife guide.

While butterfly eggs and caterpillars in various stages of growth may go easily unnoticed in your pollinator garden, you can watch for clues that your plants are hosting caterpillars while maintaining your garden.

“I watch for munch holes in the plant leaves or leaves that have been skeletonized,” Fullerton said. “And even though the leaves may be damaged I don’t really worry about the plant’s survival, especially perennial plants. Many native plants are adapted to caterpillar munching; even if leaves are destroyed, the plant will typically recover.”

“It’s like what Aaron Goodwin – one of our conservation partners – says. ‘My plants are there to be eaten.'”