One year after the Big Freeze of February 2021, we checked in with Mark Howery, a senior biologist with the Wildlife Department, to see how the arctic weather may have impacted our bird communities. Though results will be trickling in through the end of February, Howery turned to the Nation's longest-running citizen science project, the Christmas Bird Count, for an early look at winter population trends.

More than 20 Christmas Bird Count circles are monitored in Oklahoma each winter. Volunteers can visit Audubon.org to learn how to get involved with the counts.

The count, coordinated by the National Audubon Society and its predecessors since 1900, connects dedicated volunteers to a series of 15-mile diameter count circles situated across the states. Birders return to these circles each holiday season and scour their assigned territories for winter birds.

Howery, a longtime birder, has multiple connections to the count.

"I've been a participant of the Norman Christmas Bird Count for 40 years – I joined my first count when I was a teenager, the year before I could drive. And I've covered the same territory within the Norman count circle for 38 years."

Howery began coordinating the Norman count 16 years ago and has since compiled each year's observations within the count circle, reporting those numbers to the National Audubon Society. He's also a biologist with the Wildlife Department, focusing on nongame species, including many birds, for the past 29 years.

"It's easy to get lost in the numbers – in a good way," Howery said. "The Christmas Bird Count's monitoring strength is greatest at the scale of individual count circles. It's just fascinating to pore through the results of each count."

Winter Storm Recap

In its 122 years, the Christmas Bird Count has tracked bird populations through a number of droughts, rainy periods, and harsh winter storms like the one experienced in February 2021. A blast of Arctic air settled over the Southern Great Plains mid-month, breaking several weather records.

The Oklahoma Climatological Survey shared details of the weather event in its February 2021 monthly summary:

"A seasonable first few days of February soon gave way to a preliminary blast of Arctic air on Feb. 7, dropping temperatures across the state into the 20s and 30s. Several rounds of freezing drizzle provided treacherous travel conditions across the state. Temperatures continued to plummet over the next 7-10 days, culminating with historically cold air Feb. 14-16. The statewide average temperature on Feb. 15 was minus 0.7 degrees, more than 40 degrees below normal and the single coldest day statewide since at least 1915.

"Feb. 15-16 and Feb. 14-16 also set records as the coldest 2-day and 3-day periods at -0.1 degrees and 2.1 degrees, respectively. Lowest minimum and maximum temperature records fell throughout the state over those days. The record 4-day through 7-day periods were all set in Dec. 1983.

"Ninety-six of the Mesonet's 120 sites recorded their all-time record low temperature on either Feb. 15 or Feb. 16. Mesonet temperature data go back to 1997. Overnight on Feb. 16, all 120 Mesonet sites were below zero for the first time in its history."

Christmas Bird Count Caveats

Though the Christmas Bird Count can highlight changes in bird populations, Howery cautions that the results are best viewed at a decadienal scale.

"Data at the annual scale can be messy," Howery said. "The Christmas Bird Count has two natural sources of variation that affect the raw number of birds we see in a count year – weather during the individual counts, and level of survey effort."

Because coordinators are scheduling counts with multiple volunteers, dates are often set 4 – 6 weeks in advance, without the luxury of a day-to-day forecast.

"It seems we experience bad weather during the counts, which can result in a lower tally of birds, every 8 – 10 years. And in those cold or rainy years, we typically have fewer volunteers, who tend to drive along the routes and do less walking, which can also lead to a lower tally of birds."

The National Audubon Society can dampen those two variations by scaling their trends to each count's level of survey effort. But it will take time to run the numbers and add data from the 2021/2022 counts to their trend.

"Even with these disadvantages, it's the best tool we have to assess long-term changes in our winter bird populations."

Three Indicator Birds

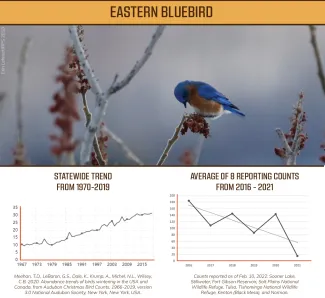

"The eastern bluebird is an ideal indicator for how this unusual weather event may have impacted some of our bird populations," Howery said.

Eastern bluebirds are Oklahoma residents and can be found in the state year-round. Since they aren't subjected to the grueling demands of migration, their populations are typically more steady. Resident birds are also not as influenced by seasonal weather that may drive or stall the migration of other species.

"When we look at the long-term trend from 1970 to 2019, we can see that the eastern bluebird has increased about 2.5% each year. Our numbers have essentially tripled in the last 50 years.

"But when we look at the raw count numbers from the past 5 – 6 years, which don't factor in the level of effort for the various counts, we see there's now a decline – and the early reports show a sharp decline for 2021."

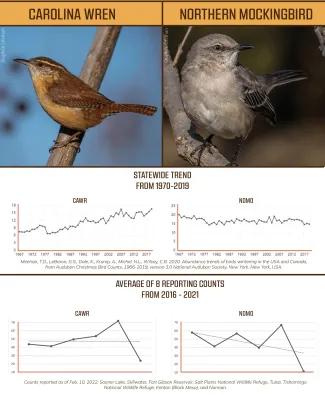

The Carolina wren and northern mockingbird, two other birds that forage primarily on insects and fruit during the winter, tell a similar story.

But the impacts of last year's winter weather is less clear for the other species.

"The cedar waxwing is a migrant, and a highly nomadic species, so any drop we see may be within the natural range of the population's variation. And any potential drops in the numbers of red-headed woodpeckers, northern flickers, and blue jays may just be related to the acorn crop.

"It may take years to see the long-term implications of last year's winter storm for those species."

Why Did the Big Freeze Hurt So Bad?

The northern cardinal, a seed-eating bird, may have been less impacted by the winter storm than other birds. Michael Bryan/RPS 2021

"This was a rare weather event; we typically only see winter storms of this severity every 50 – 100 years," Howery said. "On top of that, it hit at the end of winter when resources were at their lowest. Birds can and do handle cold temperatures. But this was a bit of a triple whammy – we had freezing temperatures; we had quite a bit of snow; and the birds were at their lowest food reserves."

Howery ranked the storm's potential level of impact based on the bird's diet.

"Seed-eating birds are fairly mobile and were in the first tier of impact. Even though a lot of the natural seeds were covered by snow, cardinals, finches, and juncos could still find seed at bird feeders.

"The second tier of impact was on fruit-eating birds. We start each winter with as much fruit as we're going to have. By the time this storm hit, most of the poison ivy and hackberry fruits were already gone.

"The last tier of impact, which was the most disadvantageous, was on insect-eating birds. Their food was buried under both snow and leaf litter, either frozen or dormant. Birds like eastern phoebes, eastern bluebirds, and Carolina wrens were then forced to compete with fruit-eating birds for leftover cedar and holly berries.

"It's hard to say, but if this storm had happened at the beginning of January, instead of the middle of February, the impact may not have been as severe."

How To Help Birds Weather the Next Storm

While many birds were blasted by the February 2021 Big Freeze, Oklahomans can help our bird communities prepare for future weather events.

"One of the biggest things we can do is improve the habitat we have control over – whether that be our own backyard, on smaller acreages, or on larger ranches," Howery said.

Like other animals, birds need food, water, and cover to survive. Native grasses, flowering or fruiting plants, and trees can meet many of those requirements. Landowners can schedule a free visit with a Wildlife Department biologist to discuss habitat potential and management options on their property. The Wildlife Department also shares plant lists and tips for smaller properties in its "Landscaping for Wildlife" online guide.

In addition to adding food-producing plants to their yards or properties, bird enthusiasts can also offer supplemental food at bird feeders, especially during severe winter storms.

"Offering seed at bird feeders is a great way to help birds weather the storm. Other foods, like suet cakes or raisins, can really benefit our fruit and insect-eating birds."

Tips for feeding and attracting birds can be found in the Wildlife Department's "Attracting Birds to Your Backyard" online guide.

People interested in bird conservation can also get involved by participating in a Christmas Bird Count, or by sharing their wildlife sightings on iNaturalist or eBird.

"As a birder, I get a lot of personal satisfaction and enjoyment from watching birds," Howery said. "But when I share my sightings, or help with a Christmas Bird Count, my observations are building on something bigger. It really creates a new purpose."