For many hunters and outdoor enthusiasts, “getting skunked” is the opposite of a good day. But for one Oklahoma State University survey team, getting skunks on camera was a critical first step in their three-year effort to learn more about the Plains spotted skunk population in southeastern Oklahoma.

The survey’s first sweet smell of success came a month after the project began in Jan. 2023, when the secretive species was detected at six camera trap sites on the Ouachita National Forest – Oklahoma Ranger District. The team would go on to detect the Plains spotted skunk at about half of their survey sites and gain insights that can help survey teams in other parts of the skunk’s range.

More About Spotted Skunks

Skunks are a familiar staple across the landscape, but few may realize Oklahoma is home to four species of the black and white carnivores. Beyond the most common striped skunk and much less common American hog-nosed skunk, two species of spotted skunk occur in the state. Though genetic studies are underway for these small, uniquely patterned animals, the Western spotted skunk is thought to occur in the Panhandle’s Black Mesa region while the Plains spotted skunk has historically been documented across much of the body of the state.

Spotted skunks are nocturnal and feed on a wide mix of food, from rabbits and mice to bird eggs and insects, and even earthworms and berries. Both species are most associated with rocky outcrops, and both are unique among skunks in that they are strong climbers that may also den in hollow trees.

“A lot of mesocarnivores, including the Plains spotted skunk, are rare or cryptic and therefore difficult to monitor,” said Danielle Brosend, the project’s graduate research assistant. “Rare, meaning they occur in low densities, or cryptic, meaning they are just hard to find because of their habits."

Motion-triggered cameras facing a bait source or scented lure are often used to detect elusive species, and these camera traps were at the heart of Brosend’s survey design. Instead of using a single camera and a single lure type, as have been used in other spotted skunk studies, Brosend clustered four trail cameras, each positioned in a different cardinal direction around a central location, and used multiple lures at each site.

“We used fatty acid tablets, a skunk-based lure, sardines, and a sweet lure made of peanut butter, jelly, molasses, anise oil, and marshmallows,” Brosend said. “This cafeteria style, where a skunk can visit whichever lure it had a preference for, is a novel approach for Plains spotted skunk surveys.”

Cameras were deployed from mid-January through mid-May, during the skunk’s mating season, and were stationed at individual sites for a minimum of 14 days. If a skunk had not been detected at a site within those 14 days, the cameras were moved to a new site at least 0.9 miles away. But if a skunk had been detected within that time frame, Brosend’s team left the cameras active at the site for an additional 21 days.

“We wanted to home in on the best methods to detect this rare and cryptic species. And then try to identify what factors drive the skunk to occupy certain sites.”

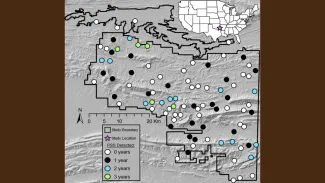

All told, Brosend’s team surveyed 91 sites on the Ouachita National Forest and nearby Wister Wildlife Management Area between 2023 and 2025. Plains spotted skunks were detected at 44 of those sites; 26 sites had positive detections in one year of the three-year survey, 13 sites had positive detections in two years, and five sites had positive detections all three years of the survey. After modeling the survey results, Brosend found that 21 days was an adequate time frame to detect a spotted skunk if it were present, and that sardines were the preferred lure.

As this is the first project to effectively test lure preference of the Plains spotted skunk and the minimum sampling time needed to detect the secretive species, the results can be used to help sampling teams in other states with their monitoring efforts. This will be especially important as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service considers a second petition to list the species under the Endangered Species Act. The first petition, submitted in 2012, when the species was still believed to be a subspecies of the Eastern spotted skunk, was dismissed in 2023 after the federal agency determined a listing was not warranted.

“It was exciting to see how broadly we detected spotted skunks throughout the Ouachita National Forest,” Brosend said. “This survey is just a snapshot of time. But based on these three years of data, the Plains spotted skunk population appears to be generally stable in this study area.”

This Plains spotted skunk survey was funded by the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service through Wildlife Restoration Grant F22AF02315 with matching resources provided by Oklahoma State University and the USGS Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit.