Jeremiah Steinert has been duck hunting most of his life and has bagged several amazing memories along the way. But this past season, he also bagged what he has called his one-in-a-million bird.

Steinert was hunting public lands in Southwest Oklahoma in Nov. 2025 when he shot what he and biologists suspect is a mallard – wood duck hybrid.

Jeremiah Steinert and dog Atlas with their “one-in-a-million” bird, a suspected mallard – wood duck hybrid.

“It wasn’t an ideal day,” Steinert recalled. “It was sunny with warm weather.” Air temperatures reached a high of 74 degrees, well above the typical 30- to 50-degree weather many duck hunters favor.

After trying his first hunting spot with no luck, Steinert moved to another area that had been intentionally flooded by biologists after late-season rains.

“This is my third season hunting that particular WMA and I’ve never seen this area flooded before. I was super ecstatic to hunt it; it looked like a birdy area.”

Two birds flew straight into the new hunting spot, and Steinert took his shot and bagged the hybrid duck. He sent his dog Atlas to retrieve the downed bird.

“Once I saw the bill, I knew it wasn’t a normal duck. The bill color was a dead giveaway.”

Atlas dropped the bird like a good boy, and Steinert immediately called his friends to ask their opinion. “Is this what I think it is?” They all agreed it may be a mallard – wood duck hybrid based on the mix of physical characteristics the bird showed.

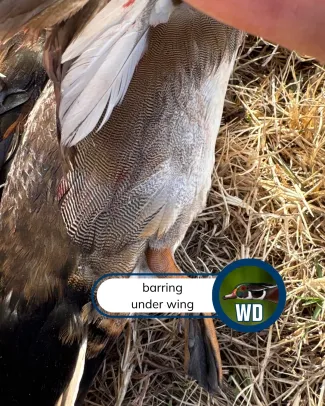

After taking a series of photos of the bird’s head, wing and breast feathers, as well as of the feet, Steinert reached out to the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation to share the story of his incredible public lands hunt.

The Science Behind Hybridization

"Hybrids are the unicorns of the natural world,” said Jason Rockwell, migratory game bird technician for the Wildlife Department. “They are something that many go without ever observing.

“The frequency of hybridization, or rarity, varies. It’s incredibly hard to accurately sample but, in general, birds are thought to have a hybridization rate of less than 0.1%.”

With that hypothesized rate, and the current mallard population estimate of nearly 6 million birds in North America, Steinert’s bird may be one of roughly 6,000 mallard hybrids. But Rockwell suspects there are likely many more on the landscape.

“The order Anseriformes, to which ducks and geese belong, has some of the highest hybridization rates of all birds. Mallards are more likely to hybridize relative to other species. They do so with other mallard-like species around the world, closely related species like pintails, not so closely related species, and even with several types of domesticated ducks that are released or have escaped from captivity. There are 39 different species with which mallards have formed a hybrid.”

What makes Steinert’s hybrid duck so interesting is the species mix.

“Mallards and wood ducks are not in the same genus, and while they share a lot of the same habitat, they have very different behaviors. For example, wood ducks nest in natural and artificial cavities high off the ground. Mallards generally nest on the ground, often in grasslands. Obviously, nesting occurs after mating, but the different behaviors make these two an even more unlikely pair.”

How Do Hybrids Happen?

“Hybrids are simply the result of mating between two different species of animals,” Rockwell said. “Most people are familiar with domesticated hybrids like mules – the result of a mated horse and donkey. In the wild it generally works the same way.”

Duck hybrids are most likely to occur when the breeding ranges of multiple species overlap, or when habitat preferences of multiple species are similar.

“This effectively puts the males and females together at the right time and place. The more closely related two ducks are at the species level, the more likely they are to be genetically compatible. Added to that, many duck species have an even and sometimes common number of chromosomes, making it easier not only for a hybrid to be created but also for the hybrid to actually be fertile.”

Though hybrids make for an interesting and natural science experiment — as well as a memorable hunt — they’re rare for a reason. Biologically, birds and many other wild animals put a lot of energy into their young to further their lineage. Because lifespans are typically shorter in wild populations, every offspring matters from a population standpoint.

“If a hybrid duckling is produced and grows to maturity but is infertile, it is the result of a lot of risk, energy, and effort on the part of a male and female pair of parent ducks,” Rockwell said. “The infertile hybrid utilized resources and — while it might have made its mother proud — it is effectively a dead end from a population level perspective. Ideally the hen would have produced viable offspring, and they would have been consuming resources for a net population gain. Instead, an entire year was lost from her productivity as it relates to the larger population.

“It can be even worse from a conservation standpoint if the hybrid is fertile. The hybridization of the mallard and American black duck has significantly affected black ducks and led to the question of whether the species is now genetically extinct. Over time, the uniqueness of one or both species can be eroded.

“Fortunately, in many cases, hybrid ducks aren’t causing great harm to the population because they are so uncommon.”

Clues to Use for Duck ID

Rockwell knows the challenges of duck identification first-hand, both as a waterfowl hunter and as the migratory game bird technician receiving “what is this” emails, calls, and texts from other hunters.

“With hybrids, it’s hard to say with 100% certainty because you are visually evaluating them all on a big spectrum. Ducks are fascinating in that they have so much diversity among species and individuals.

“But we can typically identify ducks simply by looking at their wings — when they play by the rules and aren’t hybrids. Over time, you can learn clues that really help in identification.”

Duck identification guides like the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s “Ducks at a Distance” highlight the color differences in wings, as well as differences in size, shape, wing beat, and clues that can be helpful in duck identification. Websites and apps from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Ducks Unlimited offer color photos, range maps, and even call sounds. And experienced hunters can also be great mentors for those learning to identify and hunt waterfowl. Species identification is especially important from a regulatory perspective, and hunters should be able to identify their game before pulling the trigger.

One question or clue on which seasoned duck hunters often focus is “where’s the white.” White patches tend to stand out at a distance, and their location on the bird’s head, neck, body, wings, or rump can help narrow the options for identification. Asking “where’s the white” can also help Rockwell narrow the identification of hybrids.

“Often, we see a giant patch of white in the wrong place and can immediately tell that a backyard poultry flock or a city pond is one duck short. Many times, a duck with a large amount of white feathers that seem out of place is the result of domestic duck genes.”

But natural variations like albinism and other color anomalies can also come into play.

“The first case of a leucistic black duck was confirmed in 2024. A white or blonde ‘black duck’ is certainly a complicated thing to identify. But sometimes a broader band of white or blonde-colored feathers might occur on a duck that otherwise seems identifiable as one species or another.”

For Steinert, a new DNA kit from Ducks Unlimited and the University of Texas at El Paso will take away the identification guess work. He submitted a tissue sample to duckDNA and expects to learn the heritage of his harvested duck while also contributing to the scientific knowledge about hybrid ducks.

“This was kind of a “one-in-a-million” bird,” Steinert said. “I’m excited to say the least.”

Have you had a one-in-a-million hunt? Or even your first hunt? Share photos of your harvest on the Wildlife Department’s Tailgate!