Oklahoma is known as one of the more naturally diverse states in the nation, with at least 12 ecoregions and hosting thousands of native species of vertebrates, invertebrates and vascular plants. To celebrate this incredible diversity we're putting a different spin on Opposite Day and showcasing the following opposites in Outdoor Oklahoma.

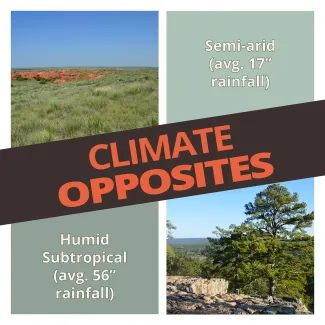

Oklahoma ranges from a humid subtropical climate in the east to a semi-arid climate in the west. Of the 50 climate variables that may be measured, rainfall is one of the more familiar. On average, the state receives 56 inches of precipitation in southeastern Oklahoma and 17 inches in the Panhandle. But in 2020, extreme rainfall ranged from 77.86 inches at the Mt. Herman Oklahoma Mesonet station to 10.16 inches at the Boise City station. This considerable difference in rainfall, along with differences in elevation, soil types and growing season length, helps shape Oklahoma's plant communities, which in turn help shape our state's diverse wildlife communities.

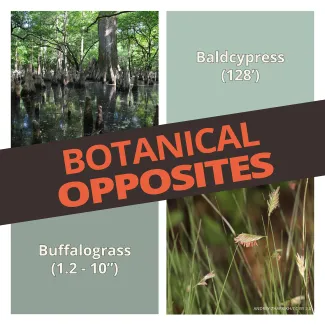

Eastern forests meet the Great Plains in Oklahoma, creating a variety of habitats and habitat structures for our state's wildlife. By and large, Oklahoma's habitat increases in stature from west to east - from buffalograss, one of our state's shortest grasses, in the shortgrass prairie, to the baldcypress, one of our state's tallest measured trees, in southeastern Oklahoma's coastal plain. These botanical opposites allow Oklahoma to host both grassland-obligate wildlife species like pronghorn and woodland-obligate wildlife species like scarlet tanagers.

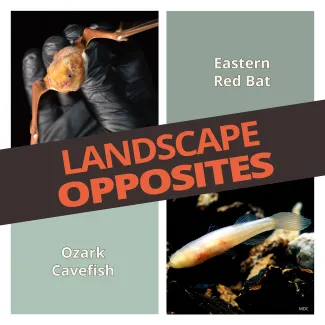

For wildlife, Oklahoma's landscape not only varies from east to west, but also from terrestrial to aquatic and from aboveground to below. Winged animals like the eastern red bat can easily take to the sky to forage and move about the state, but the federally threatened Ozark cavefish is restricted to limestone cave streams. These opposites are well-suited to their respective landscapes; a roosting or hibernating eastern red bat can be easily mistaken for a rusty oak leaf, and the Ozark cavefish, which lives most of its life in total darkness, only has rudimentary eyes.

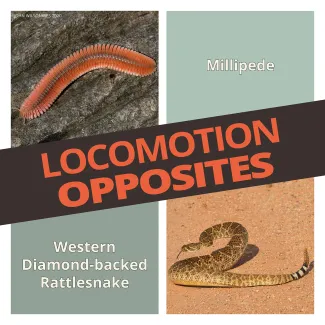

With zero legs or hundreds, our wildlife move about their landscapes in very different ways. Snakes may not have legs, but can move by bending their bodies in waves, pushing against the surface at multiple points, or slightly lifting their belly scales at several points along the body to pull themselves forward, backward or side to side. Other species like millipedes have hundreds of legs that move in a wave from the front to the back to propel themselves forward.

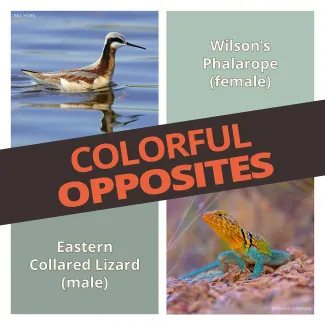

Males and females of several Oklahoma species vary in size and coloration, or are sexually dimorphic, though coloration may differ most during the breeding season. When genders vary in size or appearance, as in the eastern collared lizard, males are typically more brightly colored while females are typically more cryptic. The Wilson's phalarope is a counterexample to this general rule. In addition to being larger and more colorful, female phalaropes court and defend male mates and leave nest tending duties to the male.

Oklahoma winters may be relatively mild, but it's still cold enough, and our wildlife community diverse enough, to call for multiple winter survival strategies. Several species, including white-tailed deer, are active in Oklahoma year-round and endur colder temperatures by seasonally switching foods and finding denser shelter on colder days. Others, like the dark-eyed junco, temporarily move to Oklahoma to avoid the harsher winters typical of their more northern breeding grounds.

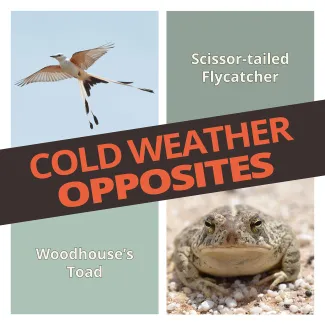

But species dependent on seasonal food sources or those that can't generate their own body heat often choose between migration and hibernation. The scissor-tailed flycatcher and other Neotropical songbirds feed largely on flying insects and must travel to warmer climates when the bulk of Oklahoma's insect community goes dormant in the fall. Many amphibians, like the Woodhouse's toad, also rely on seasonally available insects but can't make long-distance movements or regulate their internal body temperatures. Instead, these toads burrow underground and wait for warmer weather.

Share your favorite opposites found in Outdoor Oklahoma on the Wildlife Department's social media channels. Find us @OKWildlifeDept.