An early chapter in the story of Oklahoma’s dragonflies and damselflies begins at Cavanal Lake, located just outside of Wister, in southeastern Oklahoma. Months before statehood, on June 3, 1907, Bluffton, Indiana banker E.B. Williamson documented the first known Oklahoma records of 22 dragonfly and damselfly species, the highest one-day count of state odonate records, while making a brief stopover in the area.

Some of Oklahoma’s first dragonfly and damselfly records were collected at Cavanal Lake, a small lake created along the St. Louis – San Francisco Railway to power the steam engines. Today, Cavanal Lake can be accessed by the 6.5 mile Old Frisco Trail, a part of the Rails-to-Trails network.

During his party’s three-day stay in the community, Williamson also documented the first Oklahoma records of three additional dragonfly and damselfly species. From these specimens, he described multiple species he thought were new to science, but only one dragonfly, the orange shadowdragon, is still considered a full species. Another specimen collected during his trip helped to describe the damselfly now known as the vesper bluet.

“Williamson was one of the first to document Oklahoma’s dragonflies and damselflies, and quite possibly the first to do so,” said Brenda D. Smith, conservation biologist with the Oklahoma Natural Heritage Inventory.

While Williamson’s discoveries were remarkable for such a brief stopover in the state, a connection made while at Wister helped the naturalist stay involved in Oklahoma’s dragonfly world and make additional contributions after he returned to Indiana.

“Williamson met and hired a young man named Frank Collins while in Wister,” Smith said. “Collins, who lived in Indian Territory, continued to collect dragonflies along the Poteau River and around Henryetta in the summer of 1907 and later mailed the specimens to Williamson. Though he didn’t have any formal entomological training, Collins really was quite the collector.”

Collins collected the first Oklahoma records of 14 additional species and sent them to Williamson to be identified and reported. All told, Williamson and Collins collected the first Oklahoma records of 39 species of dragonflies and damselflies in 1907. That represents 22% of the state’s current odonate diversity!

Smith captured early Oklahoma records like Collins and Williamson’s, and created detailed historical and biological species accounts for each of the state’s 176 odonates in “Dragonflies at a Biogeographical Crossroads.”

Watch on TV!

To celebrate the diverse dragonfly and damselfly communities memorialized on the pages of her book, and commemorate Collins and Williamson’s discoveries, Smith journeyed to the historic site, now owned in part by the Kerr Center for Sustainable Agriculture.

“I’ve had so much fun digging into the history of Oklahoma’s odonates, and it’s a treat to come out to the place where it may have all started,” Smith said. “I think it’s really important to recognize and think about the history of organisms. We can build on the work of others in history to get trends and understand why some organisms are where there are.”

Net in hand, Brenda Smith makes her way to the edge of Cavanal Lake to commemorate a day of dragonfly discovery.

The Continued Search for Oklahoma’s Dragonflies and Damselflies

Smith has long been interested in dragonflies and was able to continue Williamson’s early work of documenting Oklahoma’s dragonfly and damselfly communities shortly after she arrived in the state. While her work has since involved other groups of animals, including tiger beetles and black rails, she’s been able to add dragonfly and damselfly records from various regions of the state while working on other projects.

“If I’m in a wetland, I’m going to be looking for dragonflies,” Smith said. “Sometimes I’m out there for a completely different reason, and it’s fun to mix taxa. I may be focused on a bird, but I can still try to add new dragonfly species or records while I’m out there.”

Smith often relies on binoculars during dragonfly field work but keeps a net at the ready in case she would like a closer look or would like to collect a potential new record.

Smith’s methods of documenting species remain similar to those of Williamson, but there have been a few changes in the century between Williamson’s expedition and Smith’s commemorative trip to Cavanal Lake.

“Because we have such a long history of specimen collection and such a long history of records in the state, I don’t need to collect as many specimens as Williamson. The strategy at the time was to collect as much as they could capture. Records show Williamson and Collins collected 583 specimens in the summer of 1907.

“Today, I can just walk around an area and identify dragonflies with binoculars and record what I see. That allows me to conduct a much more thorough search without spending a lot of time or energy capturing individuals. Someone studying dragonflies in the early 1900s would have spent 20 minutes trying to physically capture a single dragonfly, where now I can spend 20 minutes documenting multiple individuals or multiple species.”

Smith often starts her search at or near a waterbody, as dragonflies and damselflies spend much of their life underwater and remain near water as adults. She not only looks for dragonflies actively flying around, but also those perched on stalks of vegetation or on the ground.

“Males are more often associated with water. They’re territorial, and want to keep a spot open for the females to fly in. But if I’m specifically looking for females, I tend to move away from water and crash through the brush and vegetation to see if any fly out.

“It takes a lot of practice to identify dragonflies on the wing, but identification also takes a lot of patience. Sometimes it’s best to wait until the dragonfly lands to look for certain marks or features.”

Despite decades of practice and patience, Smith still gets frustrated when identifying dragonflies and damselflies.

“Some of the species near and dear to my heart are the ones I’ve spent the most time searching for. I’ve visited a lot of forested seeps looking for the Ouachita spiketail and spent a lot of time looking for the first known nymph of the Ozark emerald before finally finding one. For these species, there’s been a lot of effort made for very little data because they are so cryptic.

“But that effort can be really rewarding. It can make you feel like a Williamson. You’re learning about a species that nobody has information about. You’re learning where they may be breeding or finding the answers to other really important questions.”

Williamson’s Dragonfly Legacy Lives on in Other Naturalists

Biologists like Smith aren’t the only ones continuing Williamson’s legacy. Though a dedicated dragonfly enthusiast, Williamson was a banker by profession until the Great Depression. Similarly, other dragonfly enthusiasts have helped shape Oklahoma’s odonate story without being biologists by trade.

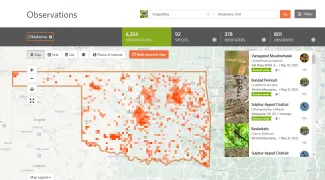

Outdoor enthusiasts have logged 92 species of dragonflies and 47 species of damselflies in Oklahoma using the popular and free iNaturalist platform. Sharing photos and sighting details allows everyday Oklahomans to continue the legacy of Williamson and the biologists that have followed in his steps.

“A lot of entomological knowledge has been built from citizen scientists,” Smith said. “We’ve collected dragonfly and damselfly records from probably 150 people in the past 13 years, many of whom have a strong interest in dragonflies but have careers in other fields.

Those 150 people have been instrumental in a larger project Smith launched in the early 2000s.

Citizen scientists have helped fill in the known distribution gaps for many of the state’s dragonflies and damselflies. Several species, including this blue dasher dragonfly, have been documented in every Oklahoma county.

“When we first started studying Oklahoma’s odonates, there wasn’t a lot of data. So, we created a spreadsheet and just started adding records from known specimens and literature references. Then we started adding as many records as we could vet from anyone who was interested in dragonflies. In 2009, this spreadsheet formally became the ‘Oklahoma Odonata Project.’ It’s since grown into an unwieldly 60,000-plus records. That’s what can happen with citizen science data.”

Because she’s seen the power of citizen science firsthand, Smith is a strong advocate for anyone interested in nature to get outside and get involved.

“People tend to think they can’t contribute because they aren’t a scientist. But just going out to a local pond and getting a species list or abundance data is worth it.

“It’s been pretty awesome to work with enthusiastic people who love nature. There’s just an energy from people who are excited to see and learn about anything.”

Smith welcomes dragonfly and damselfly questions and records to be considered for inclusion in the Oklahoma Odonata Project at argia@ou.edu. Nature enthusiasts can also share sightings of all organisms on the free platform, iNaturalist.