For many Oklahomans, the bright purple heads of thistle plants signal another addition to the ever-blooming chore list. And while the natural tendency to grab a shovel or spray bottle isn’t unfounded – more than half of the state’s 19 thistle species have been introduced, with three non-native species labeled as a “public nuisance” by state law – native thistles often suffer by association.

To weed through the prickly identification challenges associated with these plants and their look-alikes, we chatted with Amy Buthod, botanist for the Oklahoma Biological Survey.

American basketflower, a native member of the “thistle tribe,” is often mistaken for and consequently chemically treated as an invasive thistle. While the heads of basketflower are similarly colored and shaped as several invasive thistles, the plant can be distinguished by its lack of spines or “prickles” on the leaves.

“When most people think of thistles, they often think ‘purple flowers and prickly,’” Buthod said. “However, some of the species found in the ‘thistle’ plant group called Cardueae don’t necessarily have these features. For instance, the exotic yellow star and wooly distaff thistles have flowers that are yellow in color and the native American basketflower has no prickles.

“Unfortunately, there are no reliable rules for telling which species are native and which are exotic. Each species has to be examined on its own to determine its identity.”

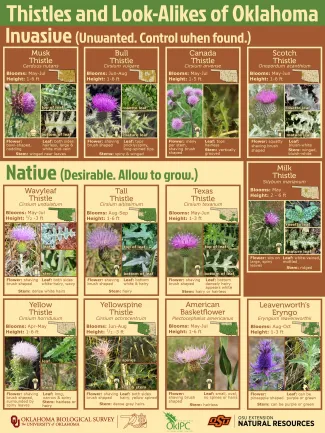

A new poster, co-created by Buthod’s agency, helps land managers and nature enthusiasts identify Oklahoma’s thistles and their look-alikes by providing photos, range maps, and bloom times of commonly encountered plants, as well as pointing out their flower shapes and characteristics of their leaves and stems.

The Oklahoma Biological Survey, Oklahoma Invasive Plant Council, and OSU Natural Resources Extension created a poster to showcase identification features and bloom times of each thistle look-alike. Free copies are available upon request.

Wildlife Benefits of Thistles

Thistles can be an important food plant for a variety of wildlife species, including pollinators and birds. While native thistle species are preferred from a conservation standpoint, the non-native species still offer pollen and seeds.

“Thistles provide great wildlife value,” Buthod said. “They provide great nectar and pollen resources for insects – monarch butterflies visit native thistle flowers more than any other wildflowers in some regions during migration. They also provide nutrient and oil-rich seeds for birds. For instance, thistle seeds make up one-third of the diet of the American goldfinch. And some thistles are hosts to butterfly larvae, like the painted lady. Many invertebrates will also use the flowers and stems as overwintering habitat.”

Native Thistles

Wavyleaf thistle growing along a Lexington WMA roadside in central Oklahoma.

Among the poster’s six native species (and one native thistle look-alike, Leavenworth’s eryngo), is the wavyleaf thistle, which can be encountered across much of Oklahoma, excluding the southeastern corner of the state. The plant blooms from May through July and has a familiar shaving brush-shaped head.

“Wavyleaf thistle is one of the easier native thistles to identify,” Buthod said. “It’s densely covered in white hairs and looks grayish green in color. And, as the name implies, the leaf margins are very wavy.”

Another of the highlighted native thistles, tall thistle, can be found across the body of the state, except for the west-central region.

“One clue for this species is the strongly bicolored leaves. They’re green on the top and hairy white on the bottom. Tall thistle can be found in semi-shady habitats, unlike most other species. It also tends to bloom much later than the others, in August and September.”

Introduced Thistles

Non-native thistles have been moving into Oklahoma since the 1920s with notable introductions of problematic species in the 1940s, 50s, and 70s.

A “noxious weed law,” passed in 2000, identifies three of the state’s introduced thistles, musk (or nodding), Scotch, and Canada, as noxious weeds that are a public nuisance in all counties across the state. The law further states “it shall be the duty of every landowner in each county to treat, control, or eradicate all Canada, musk, or Scotch thistles growing on the landowner’s land every year as shall be sufficient to prevent these thistles from going to seed.”

The noxious musk, or nodding, thistle has lobed and prickly leaves with a strong white midvein.

“Of the three noxious species, musk thistle is by far the most common in Oklahoma,” Buthod said. “This thistle has a pretty distinct rosette of leaves at its base. They are lobed and prickly with a large white midvein. Because of its height, it seems to be frequently confused with the native tall thistle.”

Another of the introduced species featured on the poster, bull thistle, can be found scattered across the body of the state and blooms from June through August.

“Bull thistle has cobwebby leaves that are toothed, or lobed, and those lobes end in a spine. Some of the leaves also have prickles on the top side.”

Thistle Motto: “I Will Survive.”

“Purple and prickly” may be an overgeneralization of Oklahoma’s thistles, but as a group, these formidable plants have stacked the odds for survival in their favor with a suite of adaptations.

- The large rosette of “typical” thistles shades the soil, reducing competition from plants that may be trying to emerge near the thistle plant.

- Some species may also release chemicals that slow or prevent the growth of neighboring plants.

- Thistle seed is wind-dispersed; individual seeds are equipped with a structure similar to that of a dandelion that allows the thistle seed to be carried through the air. These seeds may also be transported to new areas by water, other animals like birds, in hay, and even on the undercarriages of vehicles.

- Some species have spines or prickles on the leaves, stems, or structures surrounding the flowers that protect the plants from predators like grazers.

While some thistles do require a management side-eye and follow-up treatment, landowners and wildlife can benefit from native plant communities, including native thistles. Buthod hopes the poster will help landowners become more familiar with the native and invasive thistles that may occur on their properties. Dig deeper into the prickly identification challenges thistles present, check out the following webinar hosted by Buthod and the Oklahoma Invasive Plant Council. Land managers can also learn more about thistles from the OSU Extension fact sheets about thistle identification and the integrated management of invasive thistles.