Few plants demand greater respect than Texas bullnettle, and for good reason. After all, its spine-covered look can be intimidating. But the plants boast of benefits too, especially for wildlife. For bird lovers of dove, turkey, and quail, managing for bullnettle – or at least tolerating its presence – may well be worth considering.

First, any discussion about Texas bullnettle must start with its spine-like stinging hairs of which the plants have no shortage of. Although not a true stinging nettle, the stinging and itching sensation from bullnettle can last for an hour or more, so some caution is advised when working, hunting, or hiking around the plants. However, bullnettle is native to Oklahoma and quite attractive to bees, butterflies, and moths. The plants are robust too, sometimes exceeding three feet in height and/or width, offering decent cover for some smaller animals. But the greatest value of Texas bullnettle is its association within the family of plants commonly known as spurges which serve as major seed-producing plants across the state. Bullnettle’s forage value is poor, but its seeds are nutritionally rich.

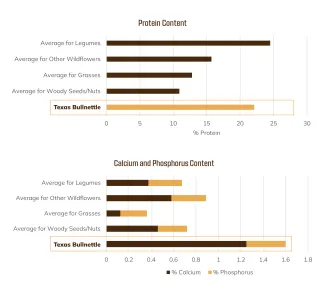

Of course, the nutritive qualities of any given plant can vary greatly. Overall, the majority of woody, grassy, and wildflower seeds are closer to average at providing all or most essential nutrients to seed-eating wildlife. Some are rich in one nutrient and low to average in others. The spurges are different, and Texas bullnettle seeds rank high in protein, calcium, and phosphorus which are critical for bird egg production and/or the growth of quail, turkey, and dove.

And we’re talking about large seeds too, exceptionally large as wildflower seeds go. As an example, it takes about 50 common ragweed seeds (the number one quail weed seed food in Oklahoma) to equal the weight of a single average-sized bullnettle seed. This means that even a single bullnettle seed can be of high value to a quail, dove, or turkey if eaten, especially during the breeding and brooding period. And quail, turkey, and dove do target the seeds when available, even to the point of being regionally important foods during some studies. In south-central Oklahoma where Texas bullnettle plants are quite common, bullnettle seeds were noted in nearly 20% of the quail crops that were investigated from 2019 to 2021.

The next question is how to manage Texas bullnettle across a property? By in large, scattered, single plants are far more common than monoculture communities where little else grows but Texas bullnettle. Therefore, control is rarely needed, especially where habitat diversity is a goal.

In general, Texas bullnettle thrives in sandy soils but can take hold in other soil types. Their massive root systems give them a competitive advantage during periods of drought and, as with many spurges, almost any type of soil disturbance can promote their establishment. Bullnettle is quite tolerant of prescribed burning during the winter months, though few studies have documented a large increase from burning. It’s also a plant that can establish and increase through the disturbance of grazing.

Overall, sandy roadsides, pastures, fields, woodlands, floodplains, and rangelands can all lay claim to a little Texas bullnettle presence and though the plants may look a bit unsightly, observing a few in areas where game birds are desired isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Plus, the seeds and large roots do have considerable wild edible value for enthusiasts looking for that sort of thing. All that’s needed – for us and for wildlife – is to get past those pesky spines!